Published November 23, 2021, Updated May, 2025

This is Part 5 of Modern JavaScript for Django Developers.

Welcome back to "Modern JavaScript for Django Developers"!

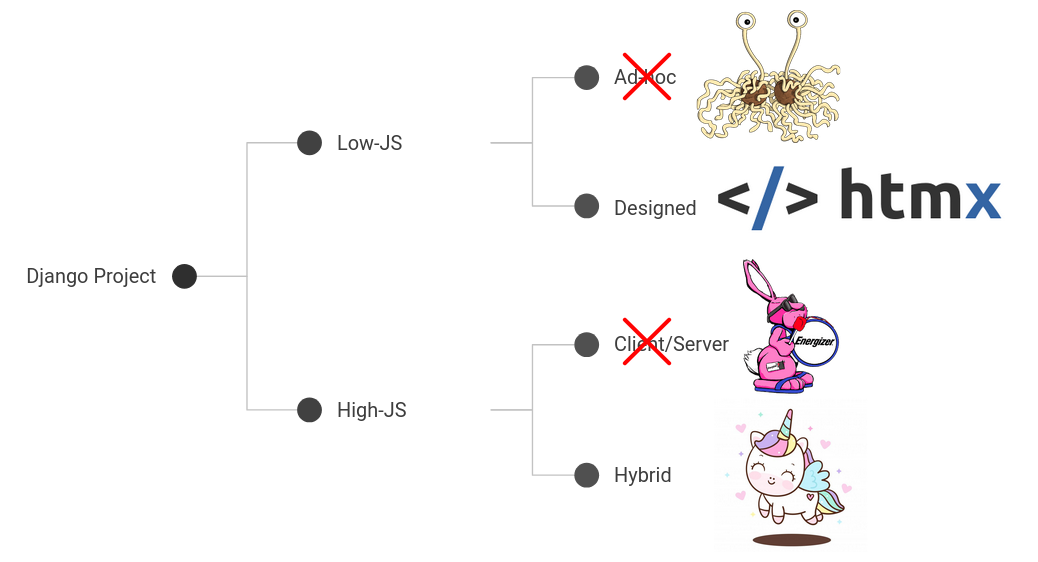

Previous installments of this series covered 1) organizing your front end code in a Django project, 2) JavaScript toolchains, 3) integrating toolchains into Django, and finally 4) integrating React and Django.

In Part 5 we’re going to take things in a new direction.

In this installment we'll turn to the low- and no-JavaScript world. We'll cover some of the common approaches to "sprinkling in" light amounts of JavaScript into your Django projects in 2021.

We’ll start high-level—approaching the big-picture questions of when you might choose a "low-JavaScript" architecture, and how to decide when to bring in a framework. After that we'll dive into two of the best low-JavaScript tools to use with Django today: Alpine.js and HTMX.

Now get cozy, put away your Webpack, React, and Vue, and get ready for some good old-fashioned server-rendered Django goodness!

Here's where we're headed:

When you might choose low-JavaScript

Before getting into any specific low-JavaScript tool you should first ask yourself: is low-JavaScript right for me?

One place to start in answering that question is understanding the type of page you're building.

In our conversation on Django front end architectures, we talked about three categories of pages you can find in almost every Django app:

- Server-first Django pages with little-to-no JavaScript. These are your standard Django pages like a login form or user profile.

- Client-first JavaScript pages with little-to-no Django. Anything with a rich and interactive front-end experience fits in this category. Think about something like Gmail or Google Maps.

- Everything in between. For example, something like this UI to sign someone up to a SaaS Subscription.

The low-JavaScript world is perfect for category 3—all of those in-between pages with a splash of page-level interactivity. But, it also works great as a compliment to mostly-server-rendered pages (category 1), and it can even work for pages that are typically be handled by something like a single page React app (category 2).

So in short—low-JavaScript is almost always an option. You'll just have to decide if and when it works well for you.

For me, low-JavaScript Django has become a more and more exciting option over time. In the last year I've found myself reaching for HTMX in many situations where I historically would have used React. It let's you do a lot of what fancy frameworks provide, and forces you to give up almost nothing in terms of how you're used to using Django.

Hopefully the rest of this guide will present a clear picture of what this looks like, and help you make the decision for your own projects.

Now let’s get into some specifics.

What problem are you trying to solve?

Before reaching for any particular tool, it’s important to know what you're trying to achieve. This might sound obvious, but it's easy to forget!

You know the saying "when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail"? Well, the same is true of technology. You can accomplish most things with any number of front-end frameworks, but they all excel at slightly different things. Using the right one for any particular problem will make you a lot more efficient!

Here are some of the reasons you might reach for JavaScript:

- Maybe you want a bit of on-page interactivity, for example, having a button open a modal dialog. We could call this making interactive interfaces.

- Or you might want to do some work asynchronously—perhaps embedding a form that sends data to your back end without doing a full-page reload. We could call this making AJAX requests.

- Or maybe you're integrating with something that already uses JavaScript—e.g. displaying your app's data in an interactive chart. We could call this using existing libraries.

These aren't the only use cases by any means, but they cover a lot of ground, so that's where we'll start. What's important is that each of these use cases have different needs—and those different needs make them uniquely suited to specific solutions. Alpine.js is great for building interactive interfaces. HTMX is amazing for AJAX. And to integrate with existing libraries we'll return to our Django JavaScript toolchain.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves. The very first question you should ask yourself is whether you need a framework at all....

To framework or not to framework

The first question that comes up for every JavaScript use case is whether—and to what extent—to reach for a framework to solve the problem.

This guide will ultimately recommend using frameworks most of the time, but to get this out of the way first: you may not need a JavaScript framework.

JavaScript—especially in a modern JavaScript environment—is powerful. You can build rich applications with vanilla JavaScript. And the existence of a vast ecosystem of 3rd-party libraries and packages—not to mention Stack Overflow—only makes it easier.

Sticking to native JavaScript is nice mostly because it’s dependency-free. This simplifies and streamlines a lot. You don’t have to worry about importing external scripts and the overhead—both in terms of page weight and code maintenance—that introduces. Your code will also be immediately understandable and modifiable by anyone who knows JavaScript (hopefully!). Frameworks—even lightweight ones—have a learning curve and can trip up developers who’ve never seen them before.

The main downside of choosing native JavaScript is that you’ll be working at a pretty low level. You end up writing a lot of code that looks something like the below. This example wires up events that close the dialog below:

// when the DOM is loaded

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

// find every element with the class "close"

(document.querySelectorAll('.close') || []).forEach((closeButton) => {

const parent = closeButton.parentNode;

// and add a "click" event listener

closeButton.addEventListener('click', () => {

// that removes the button's parent from the DOM

parent.parentNode.removeChild(parent);

});

});

});

This code isn't overwhelming or difficult to write, but it’s quite a lot of lines for something so simple. If you only need to do this a few times then sure, throw the script on your page and call it a day. But as more of these are added they will become increasingly unwieldy.

Also, it's worth pointing out that many frameworks exist primarily to make writing and maintaining code like the above easier. We'll see in the next section how we can replace the above with just a few attributes in Alpine.js—which is particularly good for this type of thing.

Introducing a framework to your project is kind of like switching from a text editor to a full-blown IDE for the first time. At first you’re slowed down, everything is unfamiliar, and you have to learn this whole new system for doing every little thing. It's frustrating! But then, once you’re on the other side of the learning curve you are way more efficient. Eventually you wonder how you ever wrote code in that clunky old way.

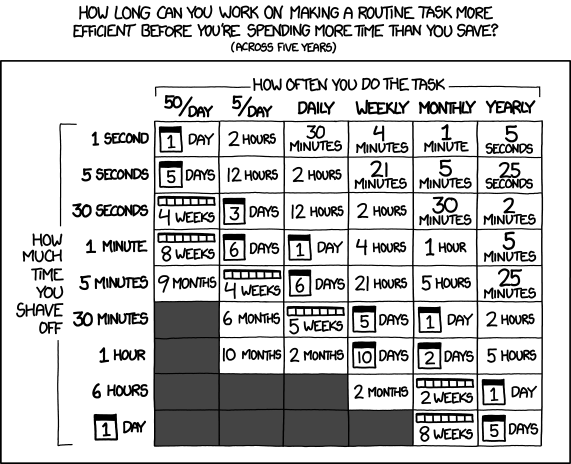

For this reason, this guide advises having a very low bar for adopting a framework. The frameworks discussed here are quick to learn and easy to adopt. And ultimately, once you get over the learning curve they will make you substantially more efficient.

Do you need a framework if your project is tiny? Absolutely not. But when things start to grow and change over time, keep the bar low for bringing one in.

With that, we're going to shift gears and focus on framework-based solutions, but know that they aren't strictly necessary!

Building interactive interfaces in your Django pages with Alpine.js

The simplest and most common use of JavaScript is for little bits of on-page interactivity: menus that open on mobile, modal dialogs that pop up and close, stuff like that. The code snippet above is a perfect example of this type of thing. You can do these with vanilla JavaScript, but it gets unwieldy quickly, so let's talk about other options.

Some UI frameworks—most notably, Bootstrap—come with many of these things built in. If you’re using one of those UI frameworks, and it supports your use case, use it! That’s what it’s there for.

Outside of UI frameworks, for a long time the default answer to interactive interfaces was jQuery. However, these days there are more popular—and franky, superior—options. The one this guide recommends starting with is Alpine.js. They even refer to themselves as "jQuery for the modern web".

Alpine is particularly good at these little utilities to help build interactive interfaces. Here’s the dialog-closing example from above using Alpine. An important point—which will come up a lot in this guide—is that it doesn't require you to write any of your own JavaScript!

<div x-data="{ open: true }" x-show="open">

<button @click="open = false">x</button>

<span>

Press the little "x" to close this message...

</span>

</div>

How does this work? Let’s go through it line-by-line.

<div x-data="{ open: true }" x-show="open">

...

</div>

This defines a <div> element with two special Alpine.js attributes on it.

- The

x-dataattribute: which defines a data property named "open" with a value oftrue. You can think of data properties like local variables in your HTML. - The

x-showattribute: which says "only show this element if the value of the "open" data property istrue."

Combined these initialize the element with "open" to true, which results in it being shown on the page.

Now let's look at the close button:

<button @click="open = false">x</button>

This markup does a variable assignment based on the "click" event.

In English, it says "when the button is clicked, set the value of the “open” property to false."

Finally, there's the message itself, which resides in the outer <div>.

Its visibility will be determined by the visibility of its parent.

<span>

Press the little "x" to close this message...

</span>

Putting this together: the page loads, "open" is set to true, and the notification shows up.

Then you click the close button, "open" becomes false and the whole thing disappears.

This is the core way that Alpine works: you define some dynamic content in terms of "local" variables, and then wire up events that manipulate those variables. Alpine attributes can set an element's visiblity, change class lists, set content, add transitions, and more. Working this way makes a lot of tasks simpler!

Also, because most logic in Alpine is configured by HTML attributes, you can do quite a lot and never even write a line of JavaScript. This simplifies things dramatically.

Integrating Alpine.js and Django

Alright, so Alpine is pretty cool. But how does it work with Django?

The quick answer is: exactly like it works with anything else.

Because Alpine lives predominantly in HTML it can work seamlessly with Django—and indeed any server-rendered template system. All you have to do is make sure that it's imported somewhere in your Django template with something like this:

<script src="//unpkg.com/alpinejs" defer></script>

And you're off to the races! This will feel very familiar to Django developers who haven't started using things like NPM and Webpack. You can adopt Alpine without worrying about all that other stuff.

Finally, since most Alpine logic happens client-side there’s really nothing specific required to make Alpine and Django work together on the backend. The Django bits become more important when you start making AJAX requests and integrating with your sever.

Which brings us to our next example...

Talking to your Django backend without a full-page reload with HTMX

After interactive interfaces, the next-most-common use of JavaScript is talking to your back end without full-page reloads—what we called making AJAX requests above. Most of these workflows follow a similar pattern—the user does something (e.g. clicks a button), a request is made to the back end, and the front end updates itself based on the response. On-page pagination, partial and auto-saving, and infinite scroll are all examples of this type of thing.

Choosing your AJAX tool

To do AJAX—as with other things—you’ve got loads of options.

Historically, you might have used jQuery’s $.ajax() function.

These days, JavaScript’s fetch,

or the axios library are more common.

All of these are perfectly fine choices.

Once again, choosing the right tool can be a complicated set of tradeoffs—many of which will depend

on the size of your project and the experience and preferences of the people building it.

Fetch is (mostly) natively supported in browsers, which means it can be used with no dependencies.

Axios provides a friendlier API (you can kind of think of it like requests for JavaScript).

Both fetch and axios play nicely with JavaScript frameworks—including React and Vue but also low-JS frameworks like Alpine.

So with that out of the way, we’ll now say: HTMX is our recommended way to do AJAX in a Django project.

What is HTMX?

Don’t feel bad if you haven’t heard of HTMX—I hadn’t until 2021. But in the last few years, HTMX has taken the Django community by storm. There were three different talks on HTMX at the 2021 DjangoCon (here, here, and here) and it also got a shout-out in my talk on “Modern Javascript and Django”.

HTMX operates similarly to Alpine, in that it’s implemented primarily by attaching attributes to your HTML markup. But where Alpine focuses on client-side state and operations, HTMX focuses on interaction with your server.

The core workflow of HTMX is: make a request to the server and swap the response into the page. At first this sounds a lot like every other AJAX workflow, but there’s a key difference: the response is returned (and rendered) as HTML.

This little detail results in a complete paradigm shift for how you do AJAX with Django. You no longer have to worry about JSON serialization, Django Rest Framework, or anything like that. Instead, your "APIs" are completely normal Django template views that return HTML. Splash in a little HTMX and presto-change-o, you have an AJAX app!

HTMX is a game-changer for the low-JS world in Django. To do it justice would require an entire standalone post—perhaps the next article in this series. But here’s a quick example that should give you the basics.

An HTMX example with Django Forms

So let’s say we want to build a little contact form. And for the purposes of our example, we’ll assume that you can contact us about anything except chimeras. Chimeras are the mortal enemies of the Pegasus!

Our Django form class for this might look something like this:

class ContactForm(forms.Form):

subject = forms.CharField(max_length=100)

message = forms.CharField(widget=forms.Textarea({'rows': 3}),

help_text='You can message me about anything you want. '

'Except chimeras. I hate chimeras.')

sender = forms.EmailField()

def clean_message(self):

# Accept any message, unless it contains the word 'chimera'

message = self.cleaned_data['message']

if 'chimera' in message.lower():

raise forms.ValidationError('What did I tell you about chimeras?!')

return message

Now, in a typical Django architecture you'd stick this form in template, serve it with a view, and process the form submission as a POST request (typically handled by the same view)—as outlined in the Django docs here. The form submission is processed as a full-page load in the browser, and the response is rendered as a new page. This is Django 101.

But what if we wanted to submit the form asynchronously—without doing a full page reload? An asynchronous workflow can have several benefits: it's a smoother user experience, allows the form to be embedded anywhere on a page, and sends less data over the wire.

First, a demo! Fill in the form below. For bonus points, see what happens if you try to use “chimera” in the message field.

Smooth, right?

Typically an AJAX workflow like this involves a fair amount of JavaScript and breaking outside of Django forms. You might serialize the data with JSON, build the UI in a JavaScript framework like React, and submit it to a Django Rest Framework endpoint.

What’s remarkable this particular example (which uses HTMX) is that:

- It is 100% backed by standard Django views and forms.

- It doesn't require writing a single line of JavaScript code.

Let’s look at how it works.

First the definition of the form:

<form hx-post="{% url 'web:contact_form' %}" hx-swap="outerHTML">

{% csrf_token %}

<p class="subtitle">Get in touch!</p>

{{ contact_form }}

<input type="submit" value="Submit">

</form>

Notice how familiar this looks!

It's almost exactly like any other Django form inside a template.

The only difference is that instead of using the standard "method" and "action" fields on the <form> tag,

we’ve instead used some htmx-specific things.

The first is hx-post. This is much like the standard “action” attribute—basically telling HTMX where to submit the form (via a POST).

In this case to the 'web:contact_form' URL.

The second is hx-swap. This tells HTMX how to “swap” in the response it gets from the form submission onto the page.

In this case replacing the outerHTML of the form itself.

Combined, these two things say: "When a user submits this form, do it as an AJAX POST to the contact_form endpoint,

and replace the form with the response you get back."

Now let’s look at that endpoint.

First a standard URL declaration:

path('htmx/contact-form/', views.contact_form, name='contact_form'),

And the view code:

def contact_form(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

form = ContactForm(request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

do_something_with_form_data(form.cleaned_data)

return render(request, 'web/htmx_contact_form_confirm.html')

else:

form = ContactForm()

return render(request, 'web/htmx_contact_form.html', {

'contact_form': form,

})

contact_form view code.

Again, this should look very familiar, because it is a completely standard Django form view. Indeed it's almost the exact same view code as the Django docs example. If the form is valid, we process the form and return a confirmation page. If the form is not valid, then we return the rendered form with errors.

What’s in the 'web/htmx_contact_form.html template?

The exact same contents as the original form definition!

HTMX swaps it into the middle of the page, so all you need to do is return the exact same thing

(with the validation errors from the POST data now included).

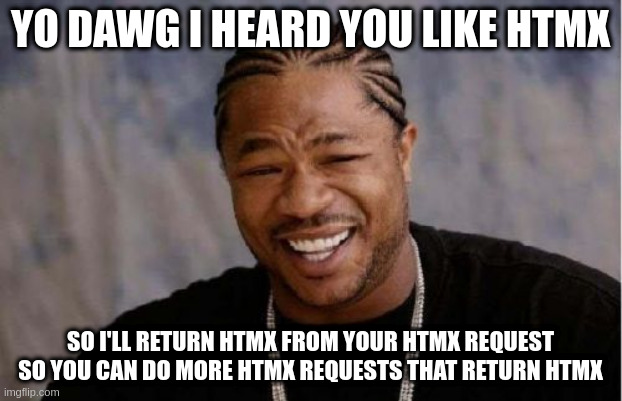

Notably, the returned form is itself another HTMX form. HTMX swapped an HTMX form for another HTMX form, and this works completely seamlessly. The recursive power of HTMX to return more HTMX is one of the most powerful aspects of using it.

The only other interesting bit of the example is the “Send Another” button on the confirmation screen, so let’s take a quick look at

the web/htmx_contact_form_confirm.html template:

<div id="contact-form-confirm">

<p>Your message was sent! Thanks!</p>

<button hx-get="{% url 'web:contact_form' %}"

hx-target="#contact-form-confirm"

hx-swap="outerHTML">

Send Another

</button>

</div>

This uses a similar pattern.

The hx-get attribute says "when this button is clicked, issue a GET request to the contact_form endpoint".

And combined, the hx-target and hx-swap attributes say "take the response and swap it into the div with ID contact-form-confirm"—the

confirmation message.

The end result is that the form gets swapped back into the right spot.

You may have noticed that the endpoint it hits is the same as the submission endpoint. Much like any other Django form, we can just serve the empty form from a GET request, and HTMX (somewhat magically) handles swapping it into the right place for us to use.

Hopefully this quick example gives a sense of the power you can achieve by combining Django and HTMX. For a more comprehensive example, with inline editing and the Django ORM, check out SaaS Pegasus—the boilerplate for launching your Django app fast. Pegasus is built by the author of this series and comes with fully-working HTMX, React, and Vue example apps, as well as loads of other code to help you learn best practices and launch a production Django application.

Conclusion: Choosing Low-JavaScript vs High-JavaScript

A year ago if you'd asked me whether you could (or should) build a serious Django application without entering the world of modern JavaScript, I probably would have said "no". But with Alpine and HTMX in the picture, I'm no longer sure. Being able to do on-page interactivity and AJAX without touching JavaScript addresses a lot of the problems that historically benefited from high-JavaScript frameworks like React or Vue.

Is JavaScript dead? Of course not. Is JavaScript inevitable? I'm no longer sure.

There are places where JavaScript is still critical—applications that have complex UI requirements or need substantial client-side state. Can you build Google Sheets or Figma without JavaScript? Of course not.

But could you build JIRA? Maybe.

And here again we come back to personal preference. JavaScript still has a lot going for it. The ecosystem of 3rd-party packages is remarkable. JavaScript developers are easy to find. Many people—believe it or not—really like JavaScript! All of these are good reasons to reach for high-JavaScript frameworks, and you'll have a perfectly good experience if you do.

But—if you're a Django developer, you love Django, and you have no interest in learning and using JavaScript—then, yeah, maybe stay in this low-JavaScript world indefinitely. It might just work out fine.

Up next: you decide!

With this post I finally feel like the "Modern JavaScript" series has achieved broad coverage of the Django/JavaScript world. And it only took 18 months!

Still, there's plenty more to say. One thing we didn't cover in this post was our third use case for JavaScript: integrating with existing JavaScript libraries. I put this use case inside the more broad category of "maintaining your own JavaScript codebase". It's a common problem, and one that having a JavaScript toolchain helps a lot with.

Also, we only scratched the surface of what you can do with Django, Alpine, and HTMX. There's a lot more to say on both of these topics, including how to build interactive forms with Alpine, and making full-blown HTMX apps. Either of these could be its own stanadlone post.

Finally, I have gotten several requests to make a Vue guide similar to the React one.

So I've decided to let the people decide! To cast your vote, fill in this form.

What should the next post be about?

Wanna guess how it's made?

'Till next time!